Marie Ondrášová

Marie Ondrášová known as Květa, née Ondrášová, born 1926, Tvorovice, Prostějov district

-

Testimony abstract

The Ondráš family with seven children lived in a small one-room house owned by the village at Tvorovice, where the father and his parents came from. They had the right of domicile there. They were the only Roma in the village and got along well with their Czech neighbours – the children played together and sometimes helped the farmers out in exchange for food. Ondrášová’s mother kept a few chickens, a goose and a duck in her small yard, and her father worked in Přerov as a builder’s labourer to earn some money. Apparently the family could not live on what the mother and children received for helping out the farmers. The younger siblings picked potatoes in the fields and helped with the beet harvest, receiving soup or “shovel-sized” vdolky (buns), not money. Marie Ondrášová took care of her younger siblings and the household while her mother helped in the fields,.

Ondrášová had a brother, Alois, born in 1933, and sisters Berta (born in 1931), Hilda (born in 1936) and Helena (born in 1939). A sister of the same name, Marie, was born a year later than the survivor (1927). It was customary in the family that the godparents had the right to choose the name, and they usually named their godchildren after themselves or their own children, and so the parents learned the name of the child only when it was brought home from the baptism. The Ondráš family had two children known as Marie, but the older one was only ever called Květa. The Ondráš children did not go to school until after the war when the youngest two sisters, Helena, and Soňa, who was born in 1942, started school.

One day a truck arrived and took them to Přerov, where many Romani people were already gathered in the school building. Marie Ondrášová, then 16, was given the task of keeping the place clean. While the other Roma had been told about the upcoming transports and had managed to prepare bread, lard and potatoes for the journey, the Ondráš family was caught unprepared. After a week, all the Romani people were transported in freight cars called “pig wagons” to Hodonín u Kunštátu. From there, the young people had to walk in three stages to the so-called Gypsy camp, while the elderly and mothers with children were taken away in trucks. On arrival, they were shaved, and women with beautiful hair had their braids cut off to make wigs. They were given striped clothes which they wore summer and winter alike. In the extreme cold, they were given something she called “black tailcoats” and walked barefoot in clogs.

The camp stood in the woods on a hillside near the road. The prisoners lived in wooden barracks surrounded by a barbed wire fence, and slept on wooden bunks, which they called cages. The bare boards were covered by a thin layer of wood shavings. There was nowhere in the camp for the prisoners to bath or wash. They were given black coffee and a piece of bread to eat in the morning. At night, the prisoners stole food from each other. Her mother used to wear a chequered scarf on her bare head, so she tied it into a bag, put bread in it and slept with it hidden under her head so that the children would have something to eat during the day. The girls went to work with children as young as six in the quarry, where they used hammers to break up the gravel, while other prisoners worked on road construction – after work they were given soup or thick porridge made from turnips, and sometimes they had a scoop of thin potato goulash. When her mother gave birth to another daughter, Soňa, in the camp, Marie Ondrášová stole milk from the churns and made white coffee for her, so she could breastfeed the child. The prisoners who worked in the kitchen had white clothing and were better off because they could cook whatever they wanted for themselves.

On a raised terrace in the corner of the camp, there were travellers’ wagons without wheels, into which they put prisoners, four or five at a time, who had typhus and no longer came to the roll call. There was no heating, everyone had just a simple blanket, and so they froze there.

Uniformed Germans and a civilian by the name of [Franz, (ed.)] Herzig once had girls from fourteen to eighteen years of age line up outside, and each of them had to show her hands and underwear. Marie Ondrášová was clean, so they chose her to help in the infirmary, even though she was illiterate. The other prisoners were then deloused – they were stripped naked, their clothes put in a large drum heated from underneath, while the women prisoners were shaved under the arms, and had their hair cut. Then they got their clothes back and the individual families were loaded into cars and taken to the trains to Kunštát and then on to Auschwitz and Ravensbrück.

The director [camp commander Štefan] Blahynka is said to have had the greatest authority in the camp, but his position was lower than that of the Germans who used to visit the camp. Ondrášová remembered him as a person who treated her decently and never harmed anyone. When he was later transferred to the camp at Lety u Píseku, he left Ondrášová in charge of his Wolfdog. According to her, they used to send gendarmes to serve in the Hodonín camp as punishment. The Germans would go around with batons and beat the prisoners, sometimes calling on the kapos, that she called “sergeants” to beat the prisoners on a bench, such as for arguing among themselves or accusing each other. The cruellest of them, according to her, were Slávek from Uničov [Jaroslav Daniel, (ed.)], Láblo [Emil Klimt, (ed.)] and Házl,[1] who had been transferred to Hodonín from another camp. They wore black clothes and had a triangle embroidered on them; they did not work, but just beat and kicked the prisoners. Házl/Házo eventually escaped from the camp. Ondrášová recalled the names of the gendarmes [Rudolf, (ed.)] Gregořica, [Antonín, (ed.)] Růžička, [Josef, (ed.)] Šrámek, [Thomas, (ed.)] Lepka, [Eduard Kohout], [Jaromír] Lukeš, and Constable [Miroslav] Výroba. Platoons of prisoners were formed[2] which guarded the other prisoners, for example at night or at work. They were said to behave even worse than the Germans. Ondrášová remembered Blažej Dydy, who was said to be as cruel as Slávek [Jaroslav Daniel], kicking people. She illustrated their cruelty in the case of the prisoner Krausová[3] , who was falsely accused by Slávek [Daniel] of catching a cat, then killing it and eating it. As punishment, she was tied to the bench and received so many blows that her flesh turned black. Ondrášová then found her in pain and suffering from fever during a routine search for the sick on the premises, and called for help from Toman[4] and Dr. [Josef (ed.)] Habanec, who excised Krausová's gangrene, so she survived.

Ondrášová wore a white coat and cap and had a sleeve marked with a red cross. Máňa [Marie] Chvalkovská from Prostějov, her sister Zuzka, and Štefka Daňhelová from Uničov worked with her on what was called the typhus ward. It was a long block in the far corner of the camp, in which the sick lay on six four-storey bunks. She used to visit them with Dr. Habanc from Olesnice and a gendarme [Miroslav] Wyroba, who had taken a nursing course. The nursing staff had been vaccinated against the disease. The prisoners with typhoid fever were divided into three groups – those on the diet called “one” were only allowed to drink or moisten their lips; those on “two” were given a little granulated sugar on their palm to lick, and the third group could get sugar and a piece of lemon. The sugar, however, caused intestinal bleeding in some patients, so they died.

Ondrášová says that Dr Habanec was very good. He came once a fortnight, asked around, checked the prisoners, and told her how to take care of them. There were also pregnant women in the camp, one of whom was her mother. Under the doctor's guidance, or rather, equipped with his advice, Ondrášová delivered the babies. She also helped her mother with the birth of little Soňa, who was the only one of the children born in the camp to survive the war. Marie Ondrášová's mother had little milk. Mrs. Klocová,[5] a friend of Marie’s mother from before the internment, lost her new-born daughter in the camp, so she offered to take care of Soňa, as she still had enough milk, and to return the little girl to her when they were released. In the end, they took her and Soňa away [to Auschwitz II Birkenau (ed.)], and when Marie Ondrášová's mother found out, Marie said she tore her hair [with grief]. In the end, Soňa spent three years in the concentration camp, but she lived to see the end of the war.

As an illiterate, Marie Ondrášová also had to learn the different types of ointments and drops, as welll as to dress wounds and take care of dead prisoners in the infirmary. The prisoners Toman[6] and Franta [František Daniel (ed.)] came when someone died. Ondrášová unlocked the morgue for them, where they wrapped the naked body in black paper and then threw it into a common grave behind the camp. They piled the bodies of the dead in a row, and afterwards, when they had sprinkled calcium hypochlorite and some earth on them, Ondrášová said the Hail Mary for the dead, but quietly, so that she would not be beaten. In rainy weather, when it was not possible to dig graves, they put the dead in the morgue, then in the corridor, or in the surgery on the table on which the prisoners were otherwise treated.

Then, when Sergeant Wyroba was in the infirmary, he allowed Ondrášová to visit her mother and siblings. He even asked her if she wanted to live with him after the war. Together with the nurses Máňa and Vlasta, Ondrášová could go outside the camp to clean the beautifully furnished huts of the guards, where their families used to pay them visits. But she never thought of running away and leaving her mother alone in the camp with the children.

When the camp began to be liquidated, Ondrášová stayed there with the gendarmes for another fortnight, packing medicines in the surgery and preparing clothes in the warehouse so that they could be taken to the camp in Svatobořice.[7] Her mother and the other children were allowed to go home; she said it was because during an investigation they admitted that they were mixed-race; Ondrášová’s maternal grandmother was German and lived with a Romani man.[8]

After the liquidation of the camp, Dr Habanec wanted to send Ondrášová to the hospital in Polička to take a midwifery course, but she refused, saying she needed to work and help her mother. She worked for a while in Olešnice at Oldřich’s meat-smoking factory for the and for the Čapeks, before going back to her mother's house after payday.[9]

Marie Ondrášová's mother returned to Tvorovice, while Marie and her sister Maruška worked for the farmer named Vrba[10] in Pivín. She said the neighbours were interested in their recent fate, and treated them normally. The Vrba family would give their mother potatoes, flour or lard when she came with a hand-cart; both daughters also gave her the money they earned so that she and her children would have something to live on. One day the gendarmes warned their mother to go to her relatives or they would take them away, so they decided to go to Slovakia to visit her eldest sister from her father's first marriage. They walked through the woods to the village below Hrozenkov, but were caught by the Germans. As they had destroyed their documents for safety, they pretended to be the Novotný family. The Germans believed them to be Czechs and handed them over to Czech police officers. One of them, Mariánek from Tvorovice,[11] recognised them and arranged to hide them in the prison at Cejl in Brno. All the gendarmes there knew about them, yet no one turned them in. A week before the end of the war, farmer Vrba, received news that the Ondráš family would be handed over to him, so he came to Cejl to get them. They went by train to Tvorovice, where the mother stayed, and then to Pivín, where the Russians were already. There was still fighting, but Marie Ondrášová and her sister managed to get home through a field full of dead soldiers.

- [1] Probably Házo, Josef Poser. (ed.)

- [2] These so-called kapos were members of the prison administration. (ed.)

- [3] Romani prisoner Marie known as Giza, née Hauerová. (ed.)

- [4] Probably the prisoner Tomáš Holomek. (ed.)

- [5] First name not given.

- [6] First name not given.

- [7] During the occupation there was an internment camp for women. (ed.)

- [8] This happened after Standartenführer Dr. M. Schulz from the Berlin Institute of Criminal Biology of the Security Police visited the SS camp in mid-July 1943, about five weeks before the transport of local prisoners to Auschwitz II - Birkenau, and subjected the selected 100 Roma prisoners to a thorough examination.

- [9] Approximately late summer 1944. (ed.)

- [10] First name not given.

- [11] First name not given.

Marie Ondrášová’s mother used to visit people who were returning from the concentration camp, and learned that Mrs. Klocová had died of cancer and that Soňa was being raised by her sister in Prague. After three years she met her again.

Marie Ondrášová sold cotton candy for twenty-five years and then cleaned various business premises. She married a man from the Raiminius family of Sinti.

How to cite abstract

Abstract of testimony from: HORVÁTHOVÁ, Jana a kol. ... to jsou těžké vzpomínky. 1. svazek. Vzpomínky Romů a Sintů na život před válkou a v protektorátu. Brno: Větrné mlýny, Muzeum romské kultury, 2021, 217-219, 336-337, 356, 375, 390, 397, 421-423, 439-440, 474-478, 495-496, 507-509, 528-532, 560, 570, 589, 590, 609-610, 619-624, 631, 691. Testimonies of the Roma and Sinti. Project of the Prague Forum for Romani Histories, https://www.romatestimonies.com/testimony/marie-kveta-ondrasova (accessed 4/19/2025) -

Origin of Testimony

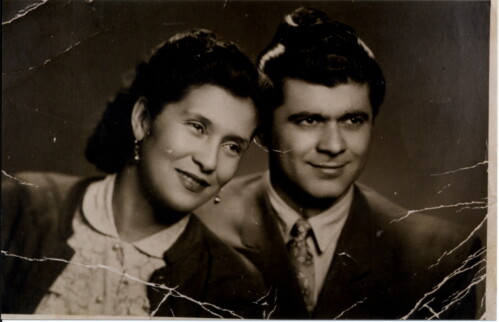

The interview with Marie Ondrášová, known as Květa, was recorded by the Museum of Romani Culture in 1997. Reference is also made to the recording of the interview, which is stored in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, for Monika Rychlíková's 2002 documentary film To jsou těžké vzpomínky (These are difficult memories), and for Ctibor Nečas' book Pamětní seznam II – Hodonín (Memorial List II – Hodonín), published by the National Pedagogical Museum and the J. The narrative is accompanied by a pre-war photograph of Marie Ondrášová at her first Communion, her portraits taken shortly after the war and post-war photographs of family members.

-

Where to find this testimony