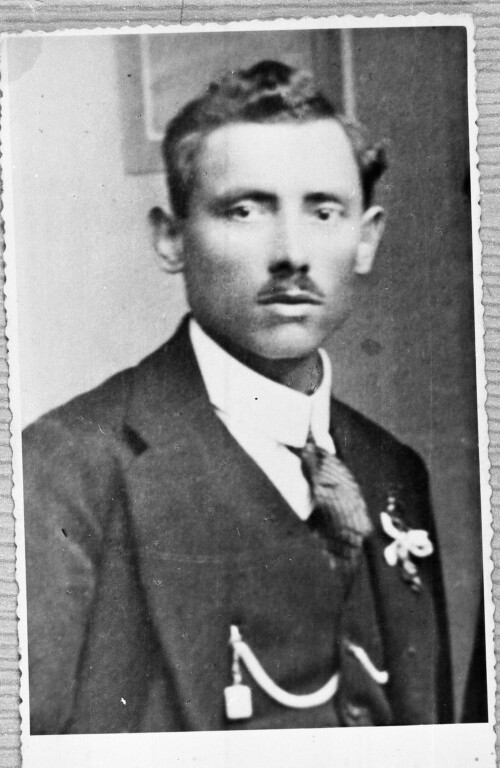

Jan Bystřický

Jan Bystřický, born 1934, Olomouc

-

Testimony abstract

The Bystřický family, which belonged to the Moravian Roma, had lived in Vyškov since the generation of Jan's grandfather. Jan Bystřický's father, Martin, was born in Hostěrádky and was a horse dealer. He was said to have been a stickler for cleanliness – when Jan Bystřický went to feed the horses as a boy, for example, he had to change his clothes outside the house, in the stable, so that the smell would not get into the house. His mother Antonia, who was a pedlar trade would also have objected. She was born at Rokytnice u Přerova into the Richter family, and her brother was Robert Richter, Berta Berousková's father. The Richters spent part of the year touring the villages with attractions such as a caterpillar ride, merry-go-rounds and swings. Jan Bystřický's father-in-law came from the Sinti family of Hauer, so the Bystřický family sometimes socialised with the Sinti, who called the settled Roma khejbri, and the Olah Roma Rumungre. His father-in-law's cousin Berousek ran the Circus Berolina.

Jan Bystřický had six siblings; although he does not mention the two sisters who did not survive the Holocaust. The oldest sibling was Antonia, who was born in 1925 and lived in Klobouky u Brna after her marriage to Vincenc Vrba. Božena was born in 1927, Antonín in 1933, and Eleonora four years later. The family lived in Vyškov, first at the gasworks[1] , then in Vyškov-Marchanice behind the railway line in a large, three-room house in the Jewish cemetery; later there was a large market garden there. Bystřický recalls that he was not afraid as a child – he and his brother used to play cards on the memorials or eat their lunch there. People from Vyškov treated the family well and respected them. As he says, they did not lead a gypsy life; for example, one of his father's brothers worked for thirty or forty years on the railway and was even supposed to become a train dispatcher, but turned it down.

DURING THE WAR

Jan Bystřický's father was a carter at Kozí horka in Vyškov.[2] His father's classmate Veselý worked there as a police chief, and he warned the Bystřický family[3] that the Gestapo would come for them next morning or in the night. The father therefore killed two or three pigs, quartered them and distributed the meat to the children in their backpacks. After that, the family hid in the Buchlov woods. One day Jan’s mother, his eldest sister and his aunt went to the village to buy bread, but a horse trader, Rybníkář, saw them and called the Gestapo. The family was sheltering from the rain under a bushy lime tree when the Gestapo drove by. They tried to escape, but were caught and taken to the prison in the village of Zdounky. About a week later, some of the family members were taken to Brno to the workhouse in Cejl, and the father, Jan Bystřický, and two uncles were taken to the prison in Cejl. They were rescued by Jan’s father's classmate [Klement] Boda, whom Bystřický referred to as the head of the workhouse. The darker-skinned members of the family – Jan, with his mother and sister – were hidden out of sight of [Franz/Josef] Herzig, who was then told that they were not Gypsies, but Moravians, and that they did not live the Gypsy life, so Herzig signed their release. About an hour later the whole family was reunited and returned to Vyškov, where they were given a village-owned house at “Noslavice”.[4]

The family however was not completely spared – the eldest, Antonie, was imprisoned from 4 August 1942 to 14 August 1942 in the so-called Gypsy Camp II in Hodonín, and her husband, Vincenc, was convicted of selling a horse on 19 March 1943 and was taken off to the Auschwitz II-Birkenau camp, where he attempted to escape with other Roma and was executed on 22 May 1943. During the war, the widowed Antonie hid a concentration camp escapee, Antonín Růžička, then fifteen years old, who later took his wife's surname and used the name Antonín Absolon.[5] Jan’s paternal uncle Ladislav also perished in Auschwitz; he was taken away on 9 May 1942 and tortured to death on 15 August 1942.

Jan Bystřický's father was a carter at Kozí horka in Vyškov.[1] His father's classmate Veselý worked there as a police chief, and he warned the Bystřický family[2] that the Gestapo would come for them next morning or in the night. The father therefore killed two or three pigs, quartered them and distributed the meat to the children in their backpacks. After that, the family hid in the Buchlov woods. One day Jan’s mother, his eldest sister and his aunt went to the village to buy bread, but a horse trader, Rybníkář, saw them and called the Gestapo. The family was sheltering from the rain under a bushy lime tree when the Gestapo drove by. They tried to escape, but were caught and taken to the prison in the village of Zdounky. About a week later, some of the family members were taken to Brno to the workhouse in Cejl, and the father, Jan Bystřický, and two uncles were taken to the prison in Cejl. They were rescued by Jan’s father's classmate [Klement] Boda, whom Bystřický referred to as the head of the workhouse. The darker-skinned members of the family – Jan, with his mother and sister – were hidden out of sight of [Franz/Josef] Herzig, who was then told that they were not Gypsies, but Moravians, and that they did not live the Gypsy life, so Herzig signed their release. About an hour later the whole family was reunited and returned to Vyškov, where they were given a village-owned house at “Noslavice”.[3]

The family however was not completely spared – the eldest, Antonie, was imprisoned from 4 August 1942 to 14 August 1942 in the so-called Gypsy Camp II in Hodonín, and her husband, Vincenc, was convicted of selling a horse on 19 March 1943 and was taken off to the Auschwitz II-Birkenau camp, where he attempted to escape with other Roma and was executed on 22 May 1943. During the war, the widowed Antonie hid a concentration camp escapee, Antonín Růžička, then fifteen years old, who later took his wife's surname and used the name Antonín Absolon.[4] Jan’s paternal uncle Ladislav also perished in Auschwitz; he was taken away on 9 May 1942 and tortured to death on 15 August 1942.

After the war they tried [Klement] Boda for collaboration with the Nazis, for his part in taking people away who were then killed. Boda's defence was that he tried to assist people to be rescued if he could. He named three families and was eventually freed.

Jan Bystřický's father traded horses until 1951. His mother was no longer allowed to follow a pedlar’s trade, but as far as Jan Bystřický remembers, she sold some cloth here and there, even under the Communists.

Bystřický worked, among other things, as a miner; he also played sports – he says that he became national boxing champion three times, representing the Czechoslovak Sokol Association, and ended his sporting career in 1952. His sister Božena married Jan Ištván after the war.[1]

The youngest sister Eleonora, known as Alena, graduated from medical school. Her married name was Kosová,[2] and she owned a fashion boutique. His brother Antonín graduated from the Archbishop's Gymnasium in Kroměříž and went on to study chemistry in Prague, but had a breakdown before graduating.

How to cite abstract

Abstract of testimony from: HORVÁTHOVÁ, Jana a kol. ... to jsou těžké vzpomínky. 1. svazek. Vzpomínky Romů a Sintů na život před válkou a v protektorátu. Brno: Větrné mlýny, Muzeum romské kultury, 2021, 130-131, 147-150, 309-313, 494-495, 648-649. Testimonies of the Roma and Sinti. Project of the Prague Forum for Romani Histories, https://www.romatestimonies.com/testimony/jan-bystricky (accessed 10/22/2025) -

Origin of Testimony

The interview with Jan Bystřický was recorded by the Museum of Romani Culture in Prostějov in September 2003, and included an appearance by his sister, Eleonora Kosová. The narrative is accompanied by a set of six family photographs from the 1930s to 2003.

-

Where to find this testimony